Remembrance is resurrection.

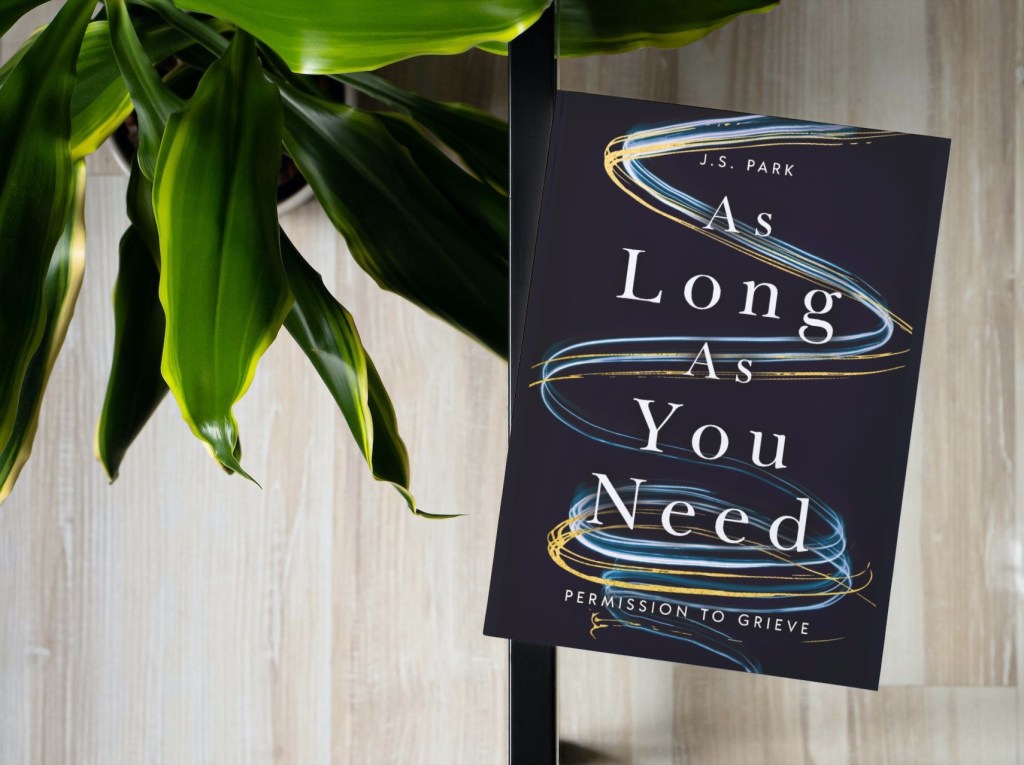

An excerpt of my audiobook for As Long As You Need: Permission to Grieve. On remembering the dead and bringing them back to life.

Remembrance is resurrection.

An excerpt of my audiobook for As Long As You Need: Permission to Grieve. On remembering the dead and bringing them back to life.

I am very happy to share that my book As Long As You Need received a star review by Publishers Weekly. I’m told this is rare, given to about 5% of tens of thousands of books.

I’m really, truly, sincerely blown away.

Book releases on April 16th. 🙌

AsLongAsYouNeedBook.com

—

Here is the book trailer:

Book title and cover reveal:

• As Long As You Need: Permission to Grieve •

You can now preorder ![]()

•

My book releases on April 16th, 2024.

It’s about grief.

I talk about my hospital chaplain work and multiple dimensions of grief, such as loss of:

/ dreams / mental health / autonomy / community / self-worth after abuse /

I dismantle myths about grief,

share stories from the hospital,

and share what I learned and unlearned from sitting with hundreds of patients.

And it is partially a memoir of my own grief: the death of my friend John, witnessing my wife survive PPD, witnessing the hardest losses on the frontlines, the loss of my faith (and coming back to it, sort of), and confronting my own history of trauma through EMDR. ![]()

•

Second to last photo is my co-author. I always had an open door policy when I was writing. Any time she dropped in, I paused and spent time with her. She’d watch me write or ask me to read it to her or just vibe to the lo-fi. She now calls lo-fi “daddy’s writing music.”

•

Last photo is me after recording some of the audiobook. I didn’t get to narrate my last one (I was told I failed the audition). My new publisher assured me from the start that I’d get to record for this one. Very glad and grateful and honored to be reading my book for you. ![]()

•

This book could not have been written without you. Online family. Your kindness, comments, messages, stories, and feedback were my strength as I took on this emotionally challenging work.

I’ll be doing a few readings randomly in April and May. Would love to meet you. ![]()

•

A special thank you to Faith M Karimi, CNN digital senior writer, for writing the article about me and my work. I got a lot of interest in a book after the article. From phone calls at the hospital to hundreds of messages, I heard from so many sharing their grief stories. I’m reminded that even when it seems like grief is a scary topic, many of us really do want to talk about loss, death, and dying. In this very tough space, I hope to meet you there.

— J.S.

Hello online family. I am very happy to share that I was interviewed by CNN journalist Faith M Karimi about my hospital chaplain work. Thank you Faith for interviewing me and our amazing palliative physician Dr. Tuch about our care for our patients. Very grateful for my fellow chaplains and healthcare workers.

Full interview: https://www.cnn.com/2023/09/18/health/hospital-chaplain-lessons-wellness-cec/index.html

I have to tell you this story about “Ray,” who thought he didn’t deserve help.

I used to work at a nonprofit charity for the homeless and I met Ray when he finally got housing and landed a new job. But he needed a new tool belt.

My friend heard about his situation and bought a tool belt for Ray. A fifteen-pocket leather carpenter pouch, one of the nicest ones you could buy. Ray was beside himself.

A few weeks later, somebody asked Ray how he liked the tool belt.

“I haven’t used it,” he said. “I’m not sure that I can. I don’t deserve a thing like that.”

He thought he would ruin it with himself. “The things I’ve done,” he said, “pretty much disqualify me. I feel guilty.”

Ray had told us his story before: addictions, abuse, abandonment. He never had a chance, a lap behind from the start, stuck in systemic structures beyond him. He felt he deserved his fate. But Ray learned to believe a better story about himself. He didn’t need to be good enough for the gift; the gift was good enough for him. The things he had done and the things that happened to him didn’t disqualify him from what was good. Maybe Ray really was the kind of guy who didn’t deserve it. But that was the point. It was a gift. We need that sort of grace, a grace that invites us into a better story than the one we were given.

It’s true one act of kindness doesn’t dismantle a whole system. It doesn’t automatically mean we succeed. But a reminder of our dignity is the very least we need. Even as systems around us shrink us down, it never means we are small: only that we were always too big for all we were given.

I think of all the ways

our past selves

were never shown a chance

still hold us back

our bodies brutalized in headlines

our minds made hatred internalized

we believed tall tales about us

that told the whole story without us.

But all that does not see you

says nothing about you

only that they lack vision

and you are already made in an irrevocable Image.

To become someone new

often means returning to ourselves—

souls dignified, made divine,

forged in inherent worth.

And even souls inside bodies that are broke

hold a dignity that no one can revoke.

In you, I see the face of God.

— J.S.

– Partially adapted from my book The Voices We Carry –

I need to tell you this story.

When I was a pastor over ten years ago, I preached at a tiny conference and afterwards a young woman approached me. She had tears in her eyes, said she was single and anxious all the time and nearing forty years old and had “accomplished nothing.” I hurt for her.

Then suddenly—

I drew a blank on what to say. My seminary hadn’t prepared me for this. And I was scared for her. How would her church reply? Her pastor? Was this place safe? All I could do was process with her, validate her feelings, remind her of her inherent value, pray with her. Was that enough?

After I had met this young anxious woman, I changed two things.

1) I rewrote the rest of my sermons for the week.

2) I vowed to always think of this woman and others like her every time I spoke or wrote.

I knew up to then, to my own shame, I had never preached for the ones in the back row.

How could I have forgotten? I was once in the back row too. But my eagerness to keep “sound” and sound pretty and to please my professors overshadowed grace.

To this day, if anything I say does not speak to the person in the back row, to someone like me or her, it’s not worth saying. I have to remember where people really live. Hope cannot smother or bypass, but must only gently enter.

If our words only work for the well-off, able-bodied, and undisturbed, then maybe we’re

1) only speaking to popular powerful folks,

2) expecting profit from big pockets, or

3) comfortable outside reality.

I have a litmus test when new theological movements pop up. Will it matter to one of my dying patients and their families? Maybe that’s basic and unfair. But that litmus test has simplified and clarified my faith.

I still make this mistake, but always a reminder to myself: If it doesn’t work in the end, it won’t work at the start. If it doesn’t work for the wounded, it won’t make you whole. If it means a lot of arguing and posturing instead of compassion and action, I’m too tired to care. I don’t. Leave it out of the patient’s room and keep it on your platform.

Jesus is with the wounded and that’s where I want to be. Bottom line, dotted line, and end of the line.

Keep me where the people are.

— J.S.

What do you no longer believe?

What are old beliefs you grieve?

I used to believe

all anger was wrong, so I was the captain of the tone police—

until I discovered politeness is not rightness, that anger is not always hate, but hurt, and to be loving is to be fiercely angry at injustice.

I used to believe

forgiveness meant friendship and even a flicker of pain meant I hadn’t forgiven my abusers—

but I found I can forgive from afar, over a lifetime, and that the pain was not my lack of forgiveness but how deep the wound was carved.

I used to believe

that death could bring people together—

until I saw covid take hundreds of thousands of lives and not even their deaths could evoke compassion,

until I saw refugees ceaselessly die in the headlines and too many justified their demise.

I used to believe

that god was American, homophobic, emotionless, and secretly disappointed in me—

until I found God had a vision of grace far greater than our sight, an imagination that far outweighed mine.

I used to believe

my value was found in my usefulness and contribution,

instead of inherently being human,

in an irrevocable Image.

I used to believe

every pain had a purpose, a connect-the-dots lesson, a fire to refine us, a reason to teach us—

until I saw pain is pain, it is not mine to explain, and maybe the only reason it happened was evil and abuse and systems that need to be unmade.

I used to believe

my depression was from a lack of prayer or faith or moral grit or fortitude—

but my mental health only lacked the help I needed and I found that therapy and medicine were not giving up, but giving life.

I used to believe

those who looked like me chose to be silent and passive—

except we were not silent, but silenced, and we had always spoken up despite this.

I used to believe

we could never unravel lopsided power dynamics and racist systems—

until I saw heels in the dirt making moves insistent, for years they had woven new stitches by inches.

I used to believe

everything I believed

was so certain.

I grieve my certainty

but I trust the mystery, to know

there is always more unknown.

Being “right” is to be alone,

but in discovery

we walk each other home.

— J.S.

There’s a classic dispute among psychologists that’s best shown by the hair dryer story. It goes like this:

A woman believes her hair dryer is going to burn down her house. It gets to be a real problem; she’s driving back home twenty times a day. Her work life and love life and social life all take a hit.

Finally a therapist asks her, “Have you thought about just bringing the hair dryer with you?”

It works. When the fear creeps in, the woman opens her office drawer and sees the hair dryer and she’s fine.

Some psychologists see a major problem here: “Nothing was solved! She still has issues! She needs to get to the root of it!” But others say she found a solution that worked for her.

I lean toward the second camp. The problem was real to her and so was the solution. Maybe later she would get to the bottom of things. But until then, she had found a way to make it okay.

The big idea is her story was taken seriously. That was the start of her wholeness. Only when a story is fully heard is there the possibility of connection or challenge or growth.

The thing is: Too many of our injuries are real. It is not merely “in their head” or “their side of the story.” And it is not enough just to believe it happened.

Abuse, racialized trauma, mass violence, systemic failures, misogyny, manipulated power dynamics, and all the mental health issues not seemingly visible—all of these need empathy, but it doesn’t stop there. They also need presence, action, compassion, and a complete reframing of all the ways that things are done. Justice would make things so right that we would never need accountability or to convince others to “believe me.”

It is already hard enough proving my injury is real.

I have the scars to prove it.

But what I need is more than belief,

more than moved hearts, more than speech.

Theology is only complete with our hands and feet.

Psychology can diagnose and make valuable notes, but only heels in the field, in the dirt, bring us hope.

Even with all our treatment and remedies, I still need you to sit with me.

In grief, your advice is probably good, but not as good as being on the floor with me.

May your pain be mine,

and your hopes mine too.

— J.S.

Part of this post is an excerpt from my book The Voices We Carry

I share three true hospital stories which are “deleted scenes” from my upcoming book, The Voices We Carry.

— J.S.

[Stories have details changed to maintain privacy.]

Hey friends, I did a video with my publisher Moody Publishers to talk about COVID-19.

I go through five points: How to approach the pandemic from a chaplain’s perspective—dealing with our fear, with each other, and with ourselves—and I directly address those who have tested positive for COVID-19 or have lost someone to it.

I hope even a single sentence will help you through this time.

(Also, this might be the first time you’ve heard my voice or seen me in video, I apologize in advance.)

God bless and much love to each of you, friends.

— J.S.

Anonymous asked:

How do I deal with the death of a loved one?

Dear friend: I’m so sorry. A close death is one of the most difficult things you will ever experience. There’s almost no getting over it. Grief is less like a cold and more like a shadow, always lingering even in the brightest light. It gets easier, but it stays with you in all kinds of ways.

As a hospital chaplain, I have seen hundreds of people die now, and there’s no formula or plan or mantra to get you through. All the hard things you’re feeling, whether it’s numbness or waves of pain or a deep soul itchiness or a tight chest or an empty stomach or rivers of tears, are all a part of grief. You’re not crazy. You might see a random thing that will remind you of your loved one, and it will hit you in the gut. You might visit a street or see someone’s smile or hear a movie quote that reminds you of everything, and it will hit you all over again. That happens. You’re not crazy.

Continue reading “Grief Over the Death of a Loved One: To Move On or Hold On?”

It’s a crazy incredible thing to be in a place where people slow down and listen, where they hear your whole story and let you paint your full heart in the air.

I was telling one of my fellow hospital chaplains about life lately, about my health problems and secret panics and suddenly about a billion other things, every humiliating and painful and neurotic moment that had been twitching over for the longest time, and I didn’t realize how much I had bottled up in my neatly wrapped fortress. My chaplain friend never judged, only nodded, never flinched, stayed engaged. She then prayed for me, a really beautiful prayer, like cool water for bruised purple hands. And I wept. A lot. Quietly, but inside, loudly. It was a little embarrassing. But something shifted and settled and became still for a moment, like the leaves of a tree coming together after a strong wind, a momentary painting. I left lighter.

Later I visited a patient who had nearly died from a brain bleed, and when I offered prayer, the nurse grabbed me and said, “Me, too.” I took her to the side, and she whispered, “Cancer. I might have breast cancer, and I’m afraid, chaplain. I’m so damn afraid.” She clenched her teeth and tried not to weep, but I put a quick hand on her shoulder and she wept anyway. She talked. I listened. There was nothing for me to say but to be there. And maybe nothing had changed—except we were made light somehow, and together drew something bigger than us. We drew colors into the gray.

There are still places, I believe, even in a busy and unhearing time, where we can draw free. I hope to meet you there, where we are not okay, but less gray than yesterday. I hope to pray for you, that we become bigger.

Officially graduated from my year long chaplain residency. Pics of our ceremony service. Thank you and love you friends, for your prayers and encouragement. Thank you to the incredible doctors, nurses, surgeons, unit coordinators, PCTs, environmental services, and every other unsung hero of the hospital. On to more chaplaincy and the next chapter!

— J.S.

Part of my hospital chaplaincy duties is to write a reflection on how it’s going. Identities may be altered for privacy. All the writings are here.

—

No—it doesn’t always work out.

The storm doesn’t always pass.

There isn’t always closure.

Not everything will be all right.

I won’t know why.

There’s a moment in the hospital when our illusion of safety is shattered and the stark reality sets in:

Things won’t change,

they won’t get better,

there won’t be a miracle,

and there won’t be a happily ever after.

It looks like God has exited the building, and that maybe He’s not coming back, and that we will never, ever know why this awful tragedy had to happen.

Babies die. Spouses drop dead at thirty. Diseases take and they take and they take. Prayers go unanswered. Drunk drivers walk free and their victims die slowly in a fire. People die alone. Some people don’t know who they are when they die; some people don’t have a single number they can call. They’re cremated by the county without a trace.

I soon found that I was having a series of tiny panic attacks over faith, more and more disorienting, these little underground bombs that threw me into crisis and left me scrambling for answers.

After a particularly hard case where a young woman’s dad shot her mom and then himself, I came home and tried to pick up some random inspirational book from my bookcase. What I found inside was so unimaginably distant and disgusting that I nearly threw it at the wall. I went through a few more books, and words that had once comforted me were crass and trivial. I couldn’t possibly believe that any of these authors had really suffered or seen suffering. I’m sure they had—and that’s what I wanted to see. Their raw edges. Not these luxurious, over-privileged travels and extra tips on mental re-arrangement, completely removed from the wounded. I saw these first-world tales as they really were: shallow, out-of-touch, and bereft of consequence.

I was lost in the whirlwind of malheur, the pain underneath our pain. I was struck by intrapsychic grief, from the loss of what “could be” and would never come to pass. I was a wax thread in a hot oven, my old beliefs dripping and frayed.

I suddenly understood the intensity of the Psalms, all the anger and violence and whiplashes of doubt, encapsulating the moments when we can no longer un-see this garish void of the nether, the unreturned.

I wondered if maybe it was easier not to believe, because believing was so dangerously painful.

Continue reading “The Irretrievable Vacuum of Unhappily Never After.”

It’s a crazy, incredible thing to be in a place where people slow down and listen, where they hear your whole story and let you paint your full heart in the air.

I was telling one of my fellow hospital chaplains about life lately, about my health problems and secret panics and suddenly about a billion other things, every humiliating and painful and neurotic moment that had been twitching my eye for the longest time, and I didn’t realize how much I had bottled up in my neatly wrapped fortress. I was embarrassed, but my chaplain friend only nodded, never flinched, stayed engaged. She then prayed for me, a really beautiful prayer, like cool water for bruised purple hands, one of those prayers where it sounded like God was her best friend down the street. And I wept. A lot. Quietly, but inside, loudly. Something then shifted and settled and became still for a moment, like the leaves of a tree coming together after a strong wind, a momentary painting. I left lighter.

Later I visited a patient who had nearly died from a brain bleed, and when I offered prayer, the nurse grabbed me and said, “Me, too.” I took her to the side, and she whispered, “Cancer. I might have breast cancer, and I’m afraid, chaplain. I’m so damn afraid.” She clenched her teeth and tried not to weep, but I put a quick hand on her shoulder and she wept anyway. She talked. I listened. There was nothing for me to say but to be there. And maybe nothing had changed—except we were made light somehow, and together drew something bigger than us. We drew colors into the gray.

There are still places, I believe, even in a busy and unhearing time, where we can draw free. I hope to meet you there, where we are not okay, but less gray than yesterday. I hope to pray for you, that we become bigger.

— J.S.

Photo by Image Catalog, CC BY PDM

Part of my hospital chaplaincy duties is to write a reflection on how it’s going. Identities are altered for privacy. All the writings are here.

The doctor tells him in one long breath, “Your wife didn’t make it, she’s dead.”

Just like that. Irrevocable, irreversible change. I’ve seen this so many times now, the air suddenly pulled out of the room, a drawstring closed shut around the stomach, doubling over, the floor opened up and the house caving in.

“Can I … can I see her?” he asks the doctor.

The doctor points at me and tells Michael that I can take him back. The doctor leaves, and Michael says, “I can’t yet. Can you wait, chaplain?” I nod, and after some silence, I ask him, “What was your wife like?” and Michael talks for forty-five minutes, starting from their first date, down to the very second that his wife’s eyes went blank and she began seizing and ended up here.

I’m in another room, with a father of two, Felipe, whose wife Melinda is dying of cancer. She’s in her thirties. She fought for three months but that was all the fight in her; she might have a few more days. Felipe is asking if his wife can travel, so she can die with her family in Guatemala. The kids are too young to fully comprehend, but they know something is wrong, and they blink slowly at their mother, who is all lines across greenish skin, clutching a rosary and begging God to see her parents one more time.

“Can I see them?” she asks the doctor.

Another room, with a man named Sam who has just lost his wife and kids in a car accident. Drunk driver, at a stop sign, in the middle of the day. Sam was at home cooking; his wife was picking up their two daughters from school; the car had flipped over twice. The drunk driver is dead; Sam doesn’t even have the option to be angry. Sam was hospitalized because when he heard the news, he instantly had a heart attack. He keeps weeping, panicked breaths, asking to hold my hand because he doesn’t know how he can live through this. He hasn’t seen the bodies of his wife and daughters yet.

“Can I see them?” he asks me.

The patient really believed her cancer was somehow “God’s amazing plan for my life.” She went on to say the things I always hear: “He won’t give me more than I can handle. Thank God we caught it early. God is going to use this for my good.”

I get why we say these things, because we’re such creatures of story that we rush for coherence. But even when such theology is true, I want to tell her that it’s okay to say this whole ordeal is terrible and that it really hurts and that we live in a disordered, chaotic, fractured, fallen world where the current of sin devours everything, that bad things happen to model citizens, that nothing is as it’s meant to be, and the people who don’t catch the cancer early aren’t well enough to thank God for anything, and that not every pain is meant to be a spiritualized, connect-the-dots lesson as if God is some cruel teacher waiting for us to “get it.”

Pain doesn’t always have to be dressed up as a blessing in disguise. God hears our frustration about injustice and illness: for He is just as mad at suffering as we are. He doesn’t rush our grief. He bled with us, too, in absolute solidarity, and broke what breaks us in a tomb. He is the friend who meets us in our pain, yet strong enough to lead us through. I can only hope, in some small measure, to do the same.

— J.S.

I’ve been thinking about how much has changed over the last few years.

I’ve been grieving over the reactionary microcosm of social media. The fiery rhetoric. The click-baiting. The “experts.” Beirut, Paris, Syria, the two earthquakes in Nepal, the ISIL threat, the US shootings, the protests in South Korea, racial tension, the political circus, the same celebrity drama.

I’ve been expecting the same predictable cycles at every headline: the outrage, the outrage against the outrage, the ever-loving trolls, the escalating comment sections, and the sudden silence when the bandwagon has moved on. I’ve been thinking how easy it is to lose sight of the real outrage, when we truly have the right to be offended amidst the “crying wolf,” and how unfortunate it is that true pain gets drowned in the viral-seeking echo chambers that never reach across the divide, but choir-preach with buzzwords and snarky flashy lines.

I’ve been wondering if we’re really this crazy.

If we’re really this hateful.

If we’re finally in the burning wreckage of a dying age.

If we’re really this angry about the wrong things and silent about the right things.

If we’re really this lost.

I’ve been thinking about how we can get better, or if we’re beyond recovery. That maybe I should give up, and give in to the cynicism, because it’s easier.

I was with a patient in the hospital who had a blood condition. “Derrick” suffered debilitating physical pain his entire life. His knees were twisted in circles, his fingers into claws, his body turned sideways, his eyes burned with baggage. He didn’t have much longer to live. It hurt him to talk, but he wanted to talk so badly. We were face to face, and he spoke about his illness, his dreams, his hopes, his insecurities, his faith, his fears, his family. We didn’t break eye contact for over an hour.

The news was on TV and there was another awful headline. The ticker-tape was scrolling at the bottom, one thing after another. The TV caught Derrick’s eye.

He said, “I don’t understand. I don’t get how we’re still fighting. I don’t understand how we’re still so mad. I’m hurting every second, and I see the news, and people still want to hurt each other. When is it enough? I can’t even play with my kids; I can’t hold them long; I can’t work or run or laugh too loud. If I just … if I could just walk without falling into a heap, the things I would do. The things we could do, you know, and we choose this instead.”

He tried to point to the television but he barely got his arm up.

“I’ll never get better. Physically, I mean. I’m at the end of my time here. But we can get better, you know, in the way that matters. I think if we knew … if we knew we’re all hurting somehow, we might be better. We might reach for each other.”

I looked over at Derrick and he was weeping. For the world. For himself. For me. For you. For us to get better.

And I wept, too. I knew that sort of pain, that desperate burden for healing and connection. To reach across the divide.

Derrick looked at me and said, “This is what matters. Right here. You and me, this is it. Can you stay with me? Can you pray with me? Can you pray for me and the hurting people?”

Through tears, we prayed. At the end, all I could really think to say was, “God—give us hope.”

I prayed for hope against the cynicism. Hope to make the best of it. Hope to hold on in the burning wreckage. Hope that there’s still good in us. Hope that we’ll make it. Hope that we’d find each other with our tiny little time on earth.

We held hands tightly. We held onto hope.

— J.S.

For my chaplaincy, I had to answer the questions:

Where is God in the midst of suffering, loss, illness, tragedy?

Where is God for the patients?

Where is God for you?

Here’s my meager attempt to answer these very huge questions.

—

In the worst moments of our lives — the cancer, the car accident, the phone call that changes everything — I’m not always sure where God is. Even the most trusting and devout are spouting, “God’s got this” with quivering lips and a shaking voice, with the slight clench of a fist, with feverish bewilderment: because the words fall flat on the cold linoleum of the hospital.

No matter how much theology we know in our three lb. brains, it all goes out the window when the floor opens up and steals us into the abyss of loss, the irreversible before and after, and the world becomes a chaotic, unsafe place of random disaster.

I can’t say where God is.

I can only say with some certainty where God is not.

I don’t believe God is distant and detached from our pain. I don’t believe He’s gloating over us behind a glass cage. I don’t believe He uses pain to teach us a lesson. I don’t believe that trials are part of “God’s amazing plan for your life.”

I don’t believe that God is some stoic, abstract teacher who waits for us to “get it.” Pain is pain, and it hurts, and no amount of theology is going to glamorize a special reason that it happens.

Not every pain has a connect-the-dots theology. When a hurricane misses a city and everyone “praises God,” it’s only condemning the millions of people who are hit by the same storm. When a child dies of preventable diseases or drunk drivers or a genetic anomaly, there’s no curse or blame upon the child. We can’t force such a tragedy into easily quantifiable boxes. To make such a correlation, if anything, is worse than the pain itself.

The truth is that we live in loss every single second, just by the mere fact that our lives won’t turn out the way we want them to. We live within absolute suffering just by losing time on the clock in the inevitable march towards death. The hospital only puts a neon sign around the coffin that awaits us all.

But my Christian faith tells me that this is completely expected. We live on a fallen world where the thread of sin has woven its tendrils into every part of our being, and that something will always be missing. Rather than deny pain, the Christian faces it head-on and acknowledges the tension. From our grief in loss to our hunger for approval to our need for intimacy: we float in this strange limbo of discontent, where nothing is ever quite the way we want it.

At the same time: My faith holds onto the hope that total fulfillment really exists. Our pain is unbearably awful, but it actually points to our desire for a healing of everything that has ever fallen apart. The inverse irony of pain is that when we’re hurting, it conveys a contrast to a very real wholeness. It’s why pain hurts. Pain tells us that something is terribly wrong and we know it ought to be put right. Or as C.S. Lewis said, “Nothing is yet in its true form.” The very reality of suffering points to our need for an ultimate comfort and justice: for God Himself.

This means there is some perfect song on the other side of the door; a light at the end of the tunnel that fills the tunnel; a beauty that doesn’t explain our pain, but is stronger and louder and bigger than all that has happened to us. We know this because we know bad notes, we know the darkness of a tunnel, we know the scars of marred beauty. Christianity says that the only real beauty is the infinitely satisfying perfection of God, who is the only being in existence that fulfills every longing we’ve ever had for truth and beauty and wholeness.

But I believe that Christianity fulfills us not only by perfection, but also by descending. Christianity says that God became one of us, out of solidarity, to suffer with us, not as a mere deity in an abstract palace, but a flesh-dwelling person in a sand-swept desert, so that, though God is so above us, He knows what it’s like to be one of us. The Christian believes in a God who wept and bled and suffered, an infinite God who infinitely compensated for our hurt, thereby cosmically answering for our afflictions and fulfilling the deep need to be heard and known at our very worst.

This must mean that God is just as mad at suffering as we are. God must be grieving with us, too. And in fact, my Christian faith tells me that because God is mad at our pain and still perfect, we’re also allowed to be as mad as He is at the very same things.

Maybe there’s an intellectually satisfying answer why we’re suffering: but what I want is someone who relates instead of debates. This is why we get flustered when someone connects the dots on our tragedies. It’s better they get with me in the trenches.

This means my job is not to solve for the other person’s pain. It’s not to bring diagrams and flowcharts. It’s to sit inside the uncertainty and anxiety of suffering and to shout against the dark, until we have shouted ourselves out. This is when God can begin to show up at all, for at our rock-bottom, He is already there.